When we started expanding this referral-driven initiative, the biggest risk wasn’t performance.

It was data.

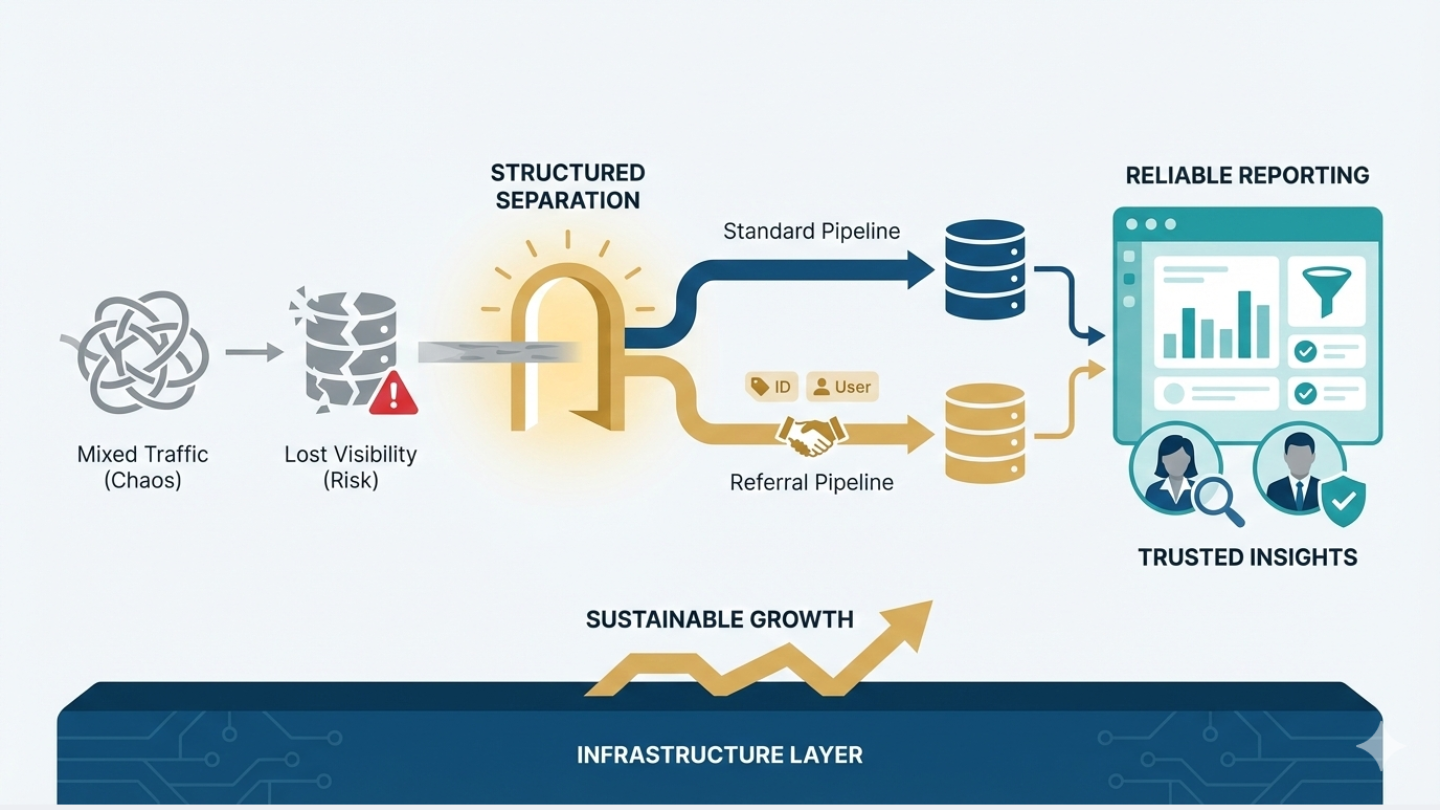

The project touched multiple teams and systems at the same time. New users were coming in through existing customers, not through standard inbound or outbound channels. Sales, marketing, and data teams all needed to understand where these users came from, how they moved through the funnel, and whether the effort was actually working. If we mixed this traffic into existing pipelines without structure, we would lose visibility almost immediately.

I had seen this happen before. Once data is blended together without clear definitions, it becomes extremely difficult to untangle later. Reporting turns into manual work. Attribution becomes subjective. And eventually, teams stop trusting the numbers altogether. For a project that was new and experimental, that was a risk we couldn’t afford.

So before thinking about scale, we focused on separation.

We created a dedicated source and environment for referred users inside our systems. These users were not treated as a variation of inbound or outbound leads. They had their own identifiers, their own tags, and a clear link back to the customer who introduced them. This made it possible to answer basic but important questions later on: which customers were driving adoption, which cohorts performed better, and where the strongest referral signals were coming from.

This structure required additional setup. New fields, new flows, and new dependencies had to be defined and mapped correctly. It wasn’t simple work, and it wasn’t especially visible from the outside. But it created a foundation that allowed sales operations and data teams to work with clarity instead of workarounds.

One of the guiding principles was empathy.

Marketing reports are often built on raw data pulled from multiple systems, stitched together with naming conventions that only make sense to the person who created them. I wanted to avoid that outcome. If the data team couldn’t easily build dashboards, or if sales leadership couldn’t quickly understand performance, the project would lose credibility regardless of results. Clean structure wasn’t just an operational preference—it was a way to make sure the work could be seen and evaluated fairly.

We also resisted the temptation to overbuild at the beginning.

Not everything needed to be ready on day one. Instead, we defined a clear MVP: a retargeting setup, a dedicated landing page, a basic one-pager, and an initial sales cadence. These were enough to validate direction without overwhelming the organization. More advanced elements—additional messaging, deeper automation, expanded materials—were layered in later, sprint by sprint, as we gathered data and feedback.

This approach helped manage expectations internally. Leadership understood that early results were directional, not final. What mattered was seeing a healthy improvement curve over time, not instant perfection. That framing made iteration easier and reduced pressure on individual teams.

Sales collaboration was handled with the same mindset.

Rather than locking sales into rigid processes, we focused on making their work easier. The structure of the cadence was designed upfront, but content was open to refinement. Sales teams brought their own experience and ideas, and when they wanted to test changes, we supported that through controlled experiments instead of ad-hoc edits. Data became the common language, which made alignment easier and removed personal bias from decisions.

From the sales perspective, this mattered. Time is money, and referred users represented real commission potential. By filtering early-stage users through automation and lifecycle design, sales teams could focus on conversations that were more likely to lead to completed transactions. Marketing ops, in this case, was not about control—it was about focus.

Looking back, none of this work was particularly flashy. There were no visible growth hacks or dramatic launches. But the system held.

Data stayed clean. Reporting stayed reliable. Teams trusted what they were seeing. And most importantly, the project could scale without creating confusion or friction behind the scenes.

That is how I think about marketing operations in practice. Not as a support function that reacts to growth, but as an infrastructure layer that allows growth to happen without breaking the organization.